Originally written for BA Curating module Seeing and Showing.

Simon Fujiwara, A Conquest – Dvir Gallery, Brussels – Exhibition Review

Bigotry: A curable disease?

A Conquest is an exhibition by Simon Fujiwara, currently on show at the commercial Dvir Gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Simon Fujiwara (b. 1982) is a British / Japanese conceptual artist based in Berlin. The exhibition explores Fujiwara’s personal experience of having contracted syphilis. The pieces are exhibited in a manner that communicates a narrative arc that begins at worship and continues to control, devastation, and ends with salvation. Through this narrative, the project humanises the taboo topic of sexually transmitted illnesses (STI) by acting as an open invitation for discussion, by using parody to question religious and historical means of societal control, and through Fujiwara’s stand in solidarity with others to have suffered the infection.

Fujiwara’s previous works have focused on themes of politics, personal and shared identity. Though A Conquest also plays on these themes, it is also a departure from his previous exhibitions. Whereas exhibitions such as Hope House and Joanne received critical acclaim for the manner with which he presented sensitive topics that he was emotionally or intellectually attached to, A Conquest is the first exhibition created by Fujiwara in which the protagonist that serves as inspiration for the works, is Fujiwara himself. This no doubt contributes to the narrative arc that one infers from his work; this exhibition is a personal account with a beginning and an end.

The exhibition’s topic and manner of its conception firmly place Fujiwara in the realms of the Avant-Garde in terms of his approach, but also the societal context in which he created his works. Fujiwara is radical and his pieces challenge the conservatism of our society; STIs are still taboo. Further, the revolutions of 1848 that proceeded the avant-garde, can be compared to the modern advancement of medicine and treatment of STIs. Whereas the former was a victory for democratic ideals that could be realised in art, the latter is a celebration of medical advancement that has been shown to reduce the internalised stigma attached to STIs and HIV in particular, through the development of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Post-1848 artists such as Delacroix, Courbet and Papety, produced radical art that espoused ‘progressive ideals’. Fujiwara’s art post-PrEP similarly heralds ‘progressive ideals’; a liberal attitude towards promiscuity that runs counter to modern society’s views.

How Fujiwara’s exhibition is housed within a polished-white cubed space, will be analysed alongside the effect of his narrative arc, and the effectiveness of his pieces in inviting a discussion that will erode the taboo of STIs, and question the power of religious and historical structures.

Dvir Gallery Brussels is situated on the first floor of Rue de la Regence 67, in a former printing house that also hosts seven other galleries. It is not a gallery for the window-shopper; one cannot stumble across Fujiwara’s exhibition; it must be sought. The stairwell from which the Dvir Gallery is entered, acts as a palate cleanser. Its neutrality prepares the eyes and mind, acting as an extended threshold over which one steps before becoming immersed in the exhibition.

Entering the gallery brings one into direct and uninterrupted contact with A Conquest, with the exhibition incorporating the foyer and four distinct rooms. The foyer holds A Conquest: Syphilis (Fig. 1), a piece that resembles a coat of arms, bringing to mind the humanising effort that Fujiwara is making. Fujiwara comments himself that, syphilis is his, ‘badge of honour’: he identifies and stands in solidarity with other sufferers. Progression through the gallery is linear, with no option but to move from room One-Four. This progression reinforces the narrative arc.

Room One is reminiscent of the central aisle of a church’s nave, imbuing the space with a ritualistic quality. Just as the central of aisle a church is defined by the placement of pews that lead to an altar, Room One – the worship phase of the narrative arc – is defined by its narrow and rectangular dimensions, at the end of which ‘Why do I have Syphilis? (A brief history) is located (Fig. 2). An antique table forms the basis of the piece, upon which by two candles are lit and a crucifix stands in centre of the surface. The ritualistic qualities of the space are exacerbated by the table’s age, the lighting, and the religious iconography, yet though Room One is where the first phase of the narrative arc is established, it is not a place where God is worshipped. Altars are created in the name of those that we are subject to; we implore with those we perceive as subjugating our self-control; the subjugator in Fujiwara’s piece, is syphilis. The piece is a record of the history of syphilis, one that denotes a sense of surrender, but also an attempt at understanding.

Separating rooms One and Two are sky blue curtains, a colour that projects both heavenly symbolism and serenity (Fig 1 & 3). The curtains are also reminiscent of the blue colouring of PrEP: the curtains serve as a reminder of the ritualistic qualities and worship of Room One, but also a promise of the STI endemics that precipitated medical advancement. Room Two – the control phase of the narrative arc – is filled with a natural light that works with the pieces to project impressions of hope and purity. SS Delirium (Fig. 3) appears to float in the centre of the room. This is the first of a three-part series of ships that describe Fujiwara’s personal journey with syphilis. SS Delirium is a reference to the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the New World, where it is posited that syphilis was contracted before being brought back to Europe. Columbus’s voyage is celebrated for his discovery, but the colonialising and economic motivations are referenced in the piece’s decoration, with reference to Lloyds bank, Visa, and the Coca-Cola company on the ship’s sails: commercialism drove Columbus and maintains a controlling grip on modern society. These appear alongside a washed rainbow motif that alludes to the LGBTQ+ community, and the slogan, ‘WE BOTH TAKE PrEP: WHAT’S YOUR RULE?’.

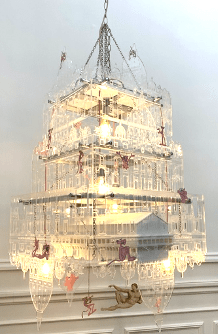

Pink Panther vs The Pope (Fig. 5) is the second piece in Room Two and appears as though a delicate, white chandelier, radiating with yellow light. The lowest hanging part of the chandelier is modelled on the Sistine Chapel. The interior is a scaled replica of Michelangelo’s famous fresco, whilst the exterior is adorned with images of the Pink Panther in what the artist describes as, ‘an epic takeover’. The dominant trimming of the chandelier is a parody of The Creation of Adam, where the image of God is replaced by an image of the Pink Panther. The piece references the societal control exerted by the Church in the 15th Century, but the insertion of popular culture results in iconoclastic imagery that treats religious control in the modern day with contempt. The piece begins a dialogue: does religion still hold the moral high ground on the subject of promiscuity?

Room Three – devastation – moves the viewer into a darker and more visceral stage of Fujiwara’s infection. The works are a raw portrayal of his experience with the disease. SS Contagion (Fig. 6) – the second of the three-part ship series – carries explicit references on its sails to sex and the gay scene of Berlin; the sails drive the viewer into the sphere of where and how Fujiwara may have contracted syphilis. The dark colourings of the ship are a stark contrast to the heavenly blue curtains separating worship and control, they evoke a sense of despair. Adjacent to SS Contagion sit the four ‘Disney-fied’ skeletons of Goya, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec and Gaugin. (Fig 7) Each are suspected of having suffered syphilis, and their Disneyfication are further examples of Fujiwara taking influence from popular culture, but in this instance to humanise the endemic. Whilst the skeletons arouse sensations of the manic, Fujiwara actually stands in solidarity with these artists, questioning if he now belongs to a select family.

Upon entering Room Four – salvation – the despair and dark colourings of the previous room are replaced by the white of purity. The Ark (Fig. 8) forms the focal point of Room Four and is Fujiwara’s modern interpretation of The Ark of the Covenant (Fig. 9). The discovery of a new covenant completes the narrative arc, with religion displaced; the Ten Commandments are replaced by a representation of penicillin – the cure for syphilis – and a new objective truth: Science. Carol Duncan wrote: ‘Secular truth became authoritative truth; religion, although guaranteed as a matter of personal freedom and choice, kept its authority only for voluntary believers.’ For Duncan, museums belong to the realm of secular knowledge and Fujiwara’s exhibition can be interpreted as a microcosm of Duncan’s views, with the viewer moving in a linear fashion from worship to the salvation of science.

The third part of the ship series is also in Room Four. The design of SS Salvation (Fig. 10) is futuristic, a yacht with sails that document Fujiwara’s visits to, and subsequent treatments, at the genitourinary medical clinic. SS Salvation conveys an overwhelming feeling of having ‘completed’ a journey.

A Conquest by Fujiwara is important. Jen Gunter wrote: ‘Why should it be any more shameful to catch an infection from sex than it is from shaking hands, a kiss or being coughed upon?’ That taboo and stigma underpin this sense of shame, necessitates a higher degree of education and conversation; A Conquest is an exhibition that invites dialogue, that questions religious and historical means of control, and utilises personal experience to offer a stand of solidarity. One may ask, if traditional systems of order and thought, are superseded by medical advancements, or if they still pervade our modern lives through the stigma that remains entrenched.

Bibliography

Duncan, Carol. “The Museum as Ritual” in Civilising Rituals: Inside Public Art, 7-20.

Oxford: Psychology Press, 1995.

Fujiwara, Simon. “Why Syphilis now?”, Essay by artist, sent out via e-mail by Dvir Gallery, April 10, 2020.

Fujiwara, Simon. (@simon.fujiwara), Instagram.

https://www.instagram.com/simon.fujiwara/

Gunter, Jen. “Why Sexually Transmitted Infections Can’t Shake Their Stigma.” New Yorker, August 13, 2019.

Howells Tom. “Simon Fujiwara delves into self-identity and scandal in ‘Joanne’.” Wallpaper, October 13, 2016.

https://www.wallpaper.com/art/simon-fujiwara-delves-into-self-identity-and-scandal-in-joanne

Jansen, Charlotte. “Simon Fujiwara brings lifesize replica of Anne Frank House to Austria.” Wallpaper, February 1, 2018.

https://www.wallpaper.com/art/simon-fujiwara-recreates-anne-frank-house

Nochlin, Linda. “The Invention of the Avant-Garde: France, 1830-1880.”, in The Politics of Vision, 1-18. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Searle, Adrian. “Simon Fujiwara: Joanne review – a weird journey out of sex scandal, via avocado,” The Guardian, October 14, 2016.

List of images

Figure 1: Simon Fujiwara, Why do I have Syphilis? (A brief history), antique table, found objects, fabric, plexiglas, metal and plastic figurines, paper, lamp, 200 x 87 x 130 cm

2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-A-Conquest-2020-installation-view-05.jpg & Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-Why-do-I-have-Syphilis_-A-brief-History-2020-mixed-media-200-x-87-x-130-cm-unique-09.jpg

Figure 2: Simon Fujiwara, Syphilis: A Conquest, plexiglass, paint, metal bolts, 180 x 120 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-A-Conquest-2020-installation-view-01.jpg

Figure 3: Simon Fujiwara, SS Delirium, mixed media, 82 x 170 x 220 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-A-Conquest-2020-installation-view-13.jpg & Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-SS-Delirium-2020-82-x-170-x-220-cm-unique-05.jpg & Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-SS-Delirium-2020-82-x-170-x-220-cm-unique-02.jpg

Figure 4: Picture of a PrEP Pill, 2020

Figure 5: Simon Fujiwara, Pink Panther vs The Pope, plexiglass, metal frame, chains, paper, light fittings, 68 x 68 x 150 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-Pink-Panther-vs-The-Pope-2020-68-x-68-x-150-cm-edition-of-5-1-AP-05.jpg & Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-Pink-Panther-vs-The-Pope-2020-68-x-68-x-150-cm-edition-of-5-1-AP-02.jpg & Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-Pink-Panther-vs-The-Pope-2020-68-x-68-x-150-cm-edition-of-5-1-AP-07.jpg

Figure 6: Simon Fujiwara, Syphilitic Comrades (Lautrec), found objects, skeleton, antique fabric, digital print on plexiglass, metal mesh, paper, paint, 43 x 52 x 90 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-Syphilic-Comrades-Lautrec-2020-43-x-52-x-90-cm-unique-04.jpg

Figure 7: Simon Fujiwara, SS Contagion, mixed media, 50 x 140 x 190 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-SS-Contagion-2020-50-x-140-x-190-cm-unique-07.jpg & https://www.instagram.com/p/B9MKT-pIX7U/

Figure 8: Simon Fujiwara, The Ark, metal plexiglass, the artist’ DNA and penicillin packaging, 60 x 80 x 130 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-The-Ark-2020-60-x-80-x-130-cm-unique-02.jpg

Figure 9: Benjamin West, Joshua passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant, oil on wood, 67.7 x 89.5 cm, 1800

Figure 10: Simon Fujiwara, SS Salvation, mixed media, 95 x 210 x 180 cm, 2020

Dvir-Simon-Fujiwara-SS-Salvation-2020-95-x-210-x-180-cm-unique-04.jpg